Is the way we talk about the human mind messing with our ability to think about it clearly?

The philosopher Colin McGinn is a tough book reviewer. He looks like a cop in an old movie about cops and robbers, and writes like one. And when he decided to take down Ray Kurzweil’s new book,How to Create a Mind: The Secret of Human Thought Revealed, he pulled no punches. First, he runs through Kurzweil’s “pattern recognition theory of the mind”:

One cannot help noting immediately that the theory echoes Kurzweil’s professional achievements as an inventor of word recognition machines: the “secret of human thought” is pattern recognition, as it is implemented in the hardware of the brain. To create a mind therefore we need to create a machine that recognizes patterns, such as letters and words. …

The process of recognition, which involves the firing of neurons in response to stimuli from the world, will typically include weightings of various features, as well as a lowering of response thresholds for probable constituents of the pattern. Thus some features will be more important than others to the recognizer, while the probability of recognizing a presented shape as an “E” will be higher if it occurs after “APPL.”

These recognizers will therefore be “intelligent,” able to anticipate and correct for poverty and distortion in the stimulus. This process mirrors our human ability to recognize a face, say, when in shadow or partially occluded or drawn in caricature.

Then the assault begins. First, McGinn states that Kurzweil’s whole theory is wrong, just on its face: “that claim seems obviously false.”

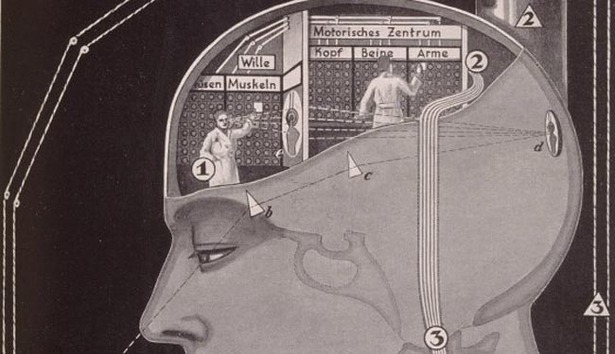

But the fascinating part of the critique is why Kurzweil’s theory can seem plausible. And that comes down to the language Kurzweil (and other people) employ in writing about neuroscience. McGinn calls it “homunculism,” the erroneous attribution of human-like qualities to pieces of a human. And it generates the illusion that we understand how synapses firing leads to an appreciation for rock ‘n roll.

[H]omunculus talk can give rise to the illusion that one is nearer to accounting for the mind, properly so-called, than one really is. If neural clumps can be characterized in psychological terms, then it looks as if we are in the right conceptual ballpark when trying to explain genuine mental phenomena–such as the recognition of words and faces by perceiving conscious subjects. But if we strip our theoretical language of psychological content, restricting ourselves to the physics and chemistry of cells, we are far from accounting for the mental phenomena we wish to explain. An army of homunculi all recognizing patterns, talking to each other, and having expectations might provide a foundation for whole-person pattern recognition; but electrochemical interactions across cell membranes are a far cry from actually consciously seeing something as the letter “A.” How do we get from pure chemistry to full-blown psychology?

Click here to read the full article

source: The Atlantic / ALEXIS C. MADRIGAL